The Puck Carrier Is Never the Last Man to Leave the Zone

The Hardest Goodbye: Learning to Let Go Without Forgetting

A month before the world shut down—before any of us had even heard the word “COVID”—my dad was in Good Samaritan Hospital in Brockton. I had just returned from a conference in Dallas, and I’m pretty sure we both had it. I was flat-out exhausted, unable to get out of bed for days. He, in turn, was bedridden in the hospital, seemingly fading.

His doctors couldn’t pinpoint anything specific. No new diagnosis. No sudden illness. But he wasn’t recovering either.

My brothers and I knew he couldn’t return to his Assisted Living apartment. He needed full-time care. Fortunately, my brother John found an available room at Newfield House, a nursing home in Plymouth.

The Nursing home itself is a throwback. When it opened in 1962, it was Plymouth's first modern nursing home. Perched atop Cannon Hill, Newfield has panoramic views of downtown Plymouth, Plymouth Bay, and the barrier beaches. In the warmer months, the gardens are spectacular, but on that February afternoon, nothing was in bloom.

In John’s words, “The place is a bit dated, but the care is great.” He was right on both accounts.

On the day of the transfer to Newfield House, my dad didn’t stir. He slept the whole way from Brockton and barely moved after being wheeled into his new room.

I should have said goodbye that day, like my brothers had, just in case. I didn’t, not because I wasn’t ready to say it, but because it didn’t feel like the end. Instead, I sat beside him in his new room, eating lunch and watching him sleep, wondering if his eyes would open, and if they did, wondering if he would be afraid.

A week ago, he was in his apartment in Sharon. Most days, when we were together, whether walking side by side around the outside of his apartment complex or grabbing a coffee, we talked about nothing or walked in silence. That was okay.

But if I fell a step behind—to say hello to someone we passed or tie my shoe—it was as if I’d vanished. And when I caught back up to him, he’d smile and say, “Oh, there you are, Markus. I was looking for you.” It never occurred to him to turn around. One moment I was beside him, the next—gone.

The same thing happened at night, when I’d tuck him in—an ultimate role reversal for a sandwich-generation parent. I’d help him to bed, pull the blanket up, say goodnight, and quietly slip out of the room. Most nights, I’d stop outside the door, pressing my ear against it. Sometimes I’d hear the soft hum of the television—just white noise to keep him company. It reminded me of those early days dropping Campbell off at daycare, peeking through the window to ensure he was okay, then walking away teary-eyed, not quite ready to leave.

That’s what I thought about when I walked away that afternoon—Dad alone in his new room at Newfield. Would he think I left him for good this time?

The following morning, his first full day at Newfield House, I was shocked to receive a text message from John showing my dad not only out of bed but sitting up in a wheelchair. Within a week, he was eating on his own and walking again.

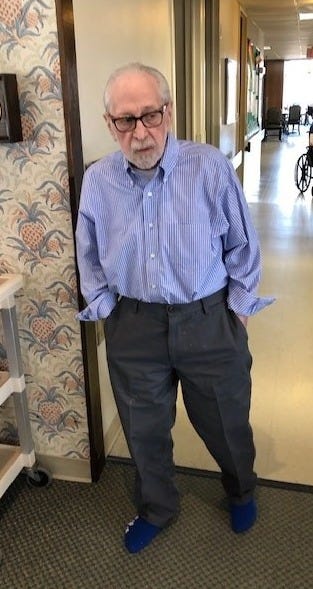

Dad wasn’t a sweatpants guy. Even at Newfield, he preferred khakis, button-downs, dress socks, and sneakers or slip-ons. In warmer months, short-sleeved shirts. He was always put together.

But once he started walking again, he added a new habit: walking around without shoes. Socks, yes. Shoes, not so much. The staff would try to get them on, but somehow they always ended up off.

Still, his face lit up every time I walked through the door. His eyes found mine—even from across the room.

It was yet another bounce back from an agonizing low point.

And that, in many ways, is the journey of Alzheimer’s: cruel, unpredictable, sometimes strangely beautiful. One moment, you're sure the worst is behind you. Next, you're preparing for another descent.

Only this time, the joy was short-lived. A month later, on March 13, 2020, the nursing home (and the rest of the world) closed its doors to visitors.

There’s simply no overstating COVID's devastation to individuals, families, and communities. We all remember the headlines—the staggering death tolls, especially in nursing homes. But just as heartbreaking were the months of isolation—the loneliness that crept in and stayed.

For my dad, that loneliness was more than a hardship. It was a slow unraveling.

He wasn’t declining physically, at least not at first. But Alzheimer’s feeds on separation. On silence. On the absence of familiar routines and faces. And as he sat confined to his room for months on end, the disease crept further in.

By the time visitors were finally allowed back into Newfield, the damage was already done—emotionally, cognitively, and spiritually.

A few months later, in October of that same year, my worst fear was realized.

When allowed back in, I visited twice weekly—Wednesdays and Saturdays. And every time I left, I’d say the same thing:

“I’ll see you [Saturday], same time, same place. Okay, bye, Dad. I love you.”

Even though visits were permitted again, we still had to keep our distance. We wore masks. So did he, or at least he tried to. His would inevitably slip off his nose and hang loosely over his mouth. By then, he was almost always in a wheelchair. His voice had grown soft—barely audible. Conversations became one-sided. Words were hard to catch. Moments were fleeting.

Those last couple of months were brutally hard.

I just wanted to sit next to him. To hold his hand. To hear him ask a question, even one that made no sense. I wanted him to tell me about his day, even if it wasn’t true. Even if it was a story I’d heard before. I wanted to feel like he was still there.

But those days were gone.

At the end of one visit, I walked him to the hallway just before Halloween. His aide stood by, ready to take him back to his room.

“Same time, same place on Wednesday, Dad?”

Nothing. No nod. No glance. No sound.

I waited.

“Okay, Dad. I love you. Bye.”

The aide turned his wheelchair around and started down the hall. Then—suddenly—he stopped.

He turned his head back toward me.

“I love you, too,” he said.

The aide looked at me. I looked at her. And we both started crying.

That was the last time he recognized me as his son.

Most mornings, as light spills through the blinds, I greet the day with a simple routine: a thank you to God, a breath, and a quiet “Hi, Dad.” It’s automatic now. He’s woven into the start of my day, even if I don’t dwell on him much after that. Unless he shows up in a dream or a memory strikes during the day, that’s usually it.

He’s been gone nearly four years. I miss him. Of course I do. Sometimes memories hit hard—like a shot to the chest—and I feel a lump in my throat. Other times, they lift me. But they never linger in the same way they used to.

I no longer feel guilty for moving forward. I don’t have to carry him with me constantly to honor his life.

The truth is, he’s still here—in the stories I tell, the lessons I share, and the moments that catch me by surprise. I just don’t carry grief like I used to. The weight has changed. It’s not something I drag around. It’s something that lifts me now.

I’ve found peace. And I’ve found deep, lasting gratitude.

You don’t forget the people who’ve shaped you.

Whether it’s my dad, my grandmother, Mr. Fogarty, or Marty—I don’t think about them every day, but when I do, it’s rarely with sorrow. It’s with warmth.

And that, I think, is what it means to move forward. You never stop remembering. But you stop clinging.

There are people on Facebook, it seems daily, posting about their loved ones who’ve passed. I comment when I can. Usually something simple, like “Hugs to you and your family.” Because honestly? That’s what I’d want if I could see my dad again.

Just one more hug.

The older I get, the more I see how fast time moves.

Erin is weeks away from graduating from Fairfield. Sean is finishing his first year at Bates, and Campbell—the little boy I dropped off at daycare and peeked at through the window to make sure he was okay—just turned 24.

Life is flying by.

But moving forward isn’t just important—it’s necessary.

If we stay stuck in grief and keep replaying the final scenes instead of writing new ones, we end up carrying their burdens, pain, and unfinished stories. And maybe that’s not ours to carry anymore. That’s not our job. Our job is to keep going, to keep growing, to live in a way that honors them—not by standing still, but by moving.

My dad would want me to move forward. Not with sadness, but with love. With purpose.

Knowing him, he would have said it this way:

“The puck carrier is never the last man to leave the zone.”

It’s one of his hockey commandments. It means: don’t hang onto the puck too long. Don’t slow down the play. When others are ahead of you, move the puck forward. Trust your teammates. Keep the game moving.

If you don’t—and you turn the puck over in your zone with no support—that’s a recipe for disaster. Or, as any goalie will tell you, one hell of a save.

I’m the puck carrier. So are you. We all carry the puck at different times in our lives. But eventually, we have to pass it.

I’ll never stop wanting to hug my dad. And yet, I still think about him. I still think about my Grammy, Marty, and Mr. Fogarty. I don’t think about them daily, but I carry them with me. Their memory doesn’t haunt me—it helps me.

We don’t leave them behind by moving forward. We carry them with us—just differently now.

What are you still holding on to—and is it time to move it forward?

So here’s to passing the puck ahead.

Same time, same place, next Tuesday?

Great story, Mark. Great lesson. I lost my younger brother 42 years ago, and not a day goes by that I don’t think about him. It’s not raw emotion like it was in the beginning, just a sweet remembering. Wondering what life would be like if he was still here today.

Last month, I lost my beautiful daughter-in-law to a very rare cancer, leaving behind my 36-year-old Fairfield graduate son and my five-year-old grandson. It’s still raw and I think of her every day, the great times we had and the great times she’ll no longer be part of. my grief is palpable, but I know I’ll eventually get to a point where I can smile instead of cry.

Both of my parents had dementia. I called that period of my life the slow goodbye. I miss them as well, but it’s different. They left a good long life. We expect our parents to die before us, but not necessarily our siblings or our child’s spouse.

You write very well. The good Fairfield Jesuits would be proud of you! Go Stags!