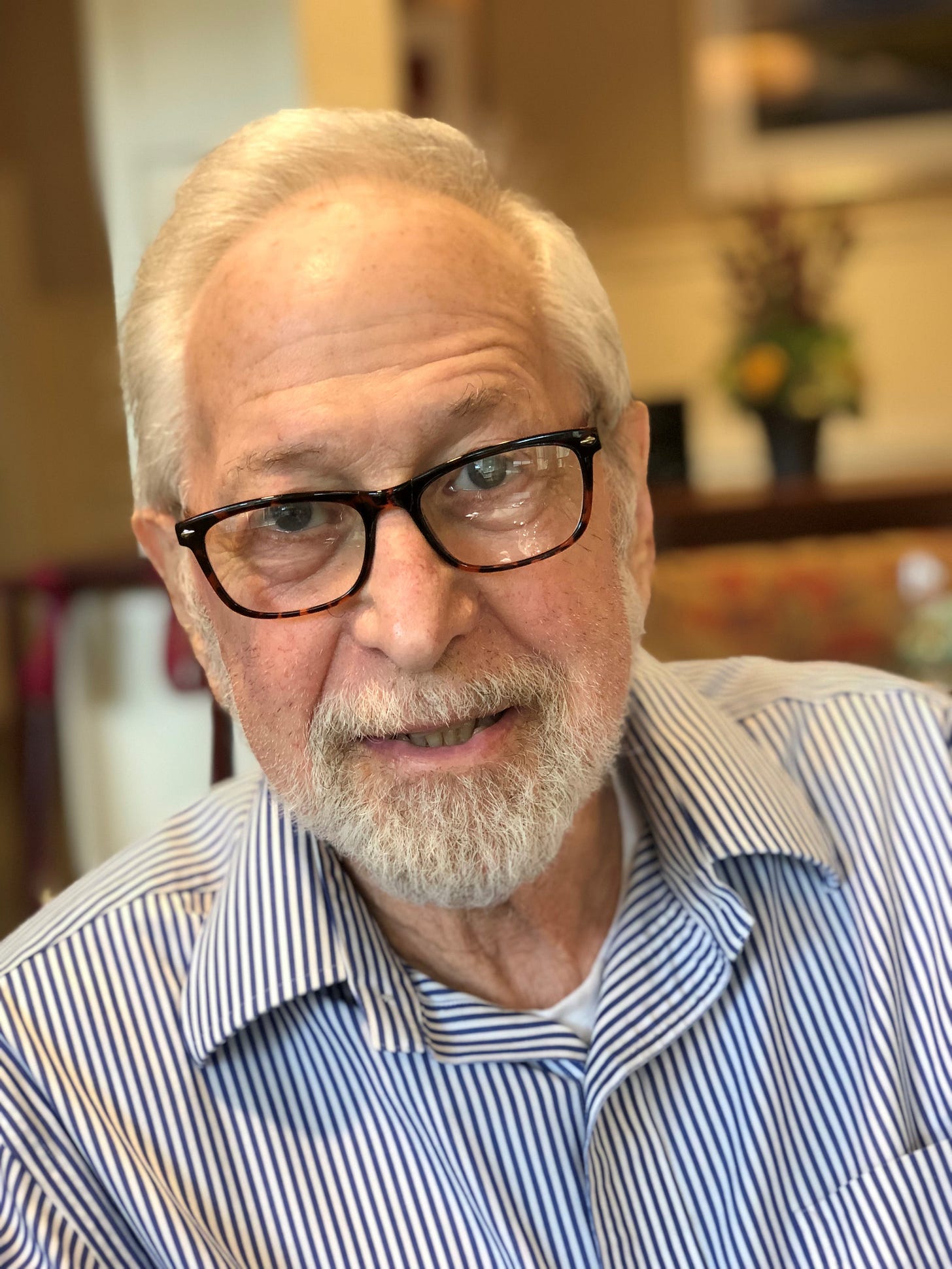

A LITTLE ABOUT ME

I always considered myself clumsy, but I don’t believe that anymore. I am careless—absolutely. I spill, tumble, and drop often, but that’s because I’m in a rush.

“I was in a rush to be born, and I’ve been in a rush to do something and be someone ever since.” (Ten Days With Dad)

I’m 52 now and more deliberate about my pace, movement, and intentions. For example, I no longer need to race down the stairs (inevitably getting my sneaker snagged on the carpet and nearly tumbling) to catch the garbage truck in the morning because I had already put the garbage out the night before. Sometimes, I still “overtask” in the kitchen because I’m late in starting on dinner, meaning I’m sauteing and dicing vegetables simultaneously. Still, I’ve learned to stop working thirty minutes sooner, so I don’t have to risk slicing a finger (which happens occasionally).

I’m not bothered by my carelessness, but I know it is unavoidable.

Over the coming newsletters, one of my goals is to better describe and articulate my transformation from BA to AA—before Alzheimer’s to after Alzheimer’s. I struggle with it, honestly. My last blog post mentioned how I want to call BS on myself. Sometimes, it sounds like my post-Alzheimer’s life is a 360-degree turnabout from before.

That’s not accurate. I’m still the same, and I’m different. Life isn’t an either/or journey. It’s most definitely an AND one.

I will leave it at this: I no longer need to do something or be someone.

COVID-19: A KINDNESS KILLER

March 13, 2020, was the day the world shut down because of COVID. I remember because it was my 48th birthday. Strange days and months followed for everyone, but two memories are forever stamped in my mind. One joyous (BLESSING) and one, well, not so much (BURDEN).

Two months into the lockdown, then-Massachusetts Governor Baker instituted a mandatory mask order within the Commonwealth. Anyone over two was required to wear masks in public retail spaces. The mask-mandate argument exasperated the political divide in our county, both in Washington, D.C., and small towns like mine.

We view this as common sense and an important way, on a statewide basis, to establish for the long term a set of standards for what we would call the new normal," Baker said.

Here’s the negative memory, as told in Ten Days With Dad:

“One morning, I was with Sean, my youngest son, getting coffee and doughnuts at the local doughnut store in Walpole. I’m a huge doughnut guy, but I had made a conscious effort to limit my doughnut intake to once a month. Well, it was my one day of the month to get my glazed chocolate stick, so I was excited.

Walking to the entrance, ahead of us were four young guys, none wearing a mask. Right away, I knew there was going to be a confrontation. Sean knew it, too. He asked me to let it go, but I couldn’t help myself. I was tired of the excessive anti-mask rhetoric and falsehoods being promoted on TV, Facebook, and at the local market.

“Excuse me,” I said to the group of guys. “Why aren’t you wearing a mask?”

They looked at one another before one said, “Because we don’t have to.”

“Actually, you do. The governor is mandating it, and there’s a sign right there on the door.”

“We don’t have to wear them if we don’t want to.”

They left the store and returned to their company truck, but I was livid. I even asked the store employee why she didn’t ask them to put on a mask.

“Well, we have a lot of seniors who come here, and some of them have difficulty wearing the mask,” she said. “So we don’t enforce it.”

Flustered and pissed off, I turned and left on the spot. Sean followed me to our car but was upset with me for saying something to the guys.

“I asked you not to say anything, but you did anyway.”

“Sean, I can’t go see Papa because of COVID. People are dying from it, and these jerks will get people sick by not wearing a mask. I don’t care if you’re mad; it’s wrong.”

Before he could reply, we heard the four guys taunting me from across the parking lot, which only annoyed and angered me further. I snapped and started yelling back at them. Sean was even more visibly upset with me. Which only made me angrier.

“Get back in your truck before you make a bigger fool of yourself,” I shouted at them.

“You’re the damn fool!”

Back and forth we went until I drove off, shouting, “I hope you all fucking get COVID!”

The brief moment of satisfaction I got from doing the right thing was immediately replaced by shame and embarrassment for my words and actions—both with my son and the teenage store employee at the doughnut shop. I was the opposite of kind; I was rude, disrespectful, and nasty. I could have conveyed my message to the young men in a manner that wasn’t hostile or aggressive. Instead, I threw civility and kindness out the window. I’m still embarrassed by my behavior almost a year later.”

I was a jerk, and the guys were jerks. COVID brought out the ugly in many of us. Even though I was halfway through my “after Alzheimer’s” transformation (AA), my internal frustrations had reached a breaking point. And they broke. Kindness on both sides went out the window. I was anything but a kindness mentor to Sean on that day.

What’s a kindness mentor?

THERE ARE MANY TYPES OF MENTORS

Having a mentor in a particular field of study or occupation can be extremely helpful. I had many when I worked in fundraising and a few as a salesman. I’ve also had kindness mentors my whole life. Mrs. McCann, my first-grade teacher, was so kind when I showed up on the first day of school with a cast on my arm that I still talk about her today. Mrs. Blake’s kind words about my writing skills to my dad are why you’re reading this book.

My dad was the ultimate kindness mentor. I can’t recall seeing him being rude, disrespectful, or mean to someone. He sometimes interrupted me to tell me what was on his mind, but not because he was rude. At the Flamingo Resort in Las Vegas, he treated everyone with kindness. (Ten Days With Dad)

There’s a fluency to kindness, the same as there is to languages, and I became fluent in kindness by watching my dad in real-time, in ways most fathers and sons never get to. My mom moved out of the house when I was seven, and I didn’t leave Beers Ave full-time until I was 22. We then became business partners in our branded merch business and worked together for nearly fourteen years. When his Alzheimer’s disease forced him into assisted living, I was with him every day. We shared more than 200 meals and 600 cups of coffee.

Be a kindness mentor to your children, spouse, and siblings. Smile more. Say hi to people you pass on the street. Hold the door open for others. Quit using the horn on your car when you’re merely frustrated. Be more patient. Reject the harmful language that people use against one another. Think before you speak. Text, email, or call someone you haven’t talked to in a while. Make breakfast for your family. Offer to pay the dinner check. Write a handwritten note to a friend. Take out the garbage. Stop judging others. Stand up to bullies. Say please and thank you. Ask someone how you can help them.

And let’s not forget to be kind to ourselves, too. There are enough people in this world who will try to beat you up—there’s no need for you to do the same.

The second impressionable lockdown memory, the BLESSING, was being confined to our homes for nearly four months. Sure, scrambling for toilet paper stunk, but the lockdown allowed Coleen and me to enjoy 98 consecutive dinners with our three teenagers. In my mind, I can easily recall the smell of sourdough bread after leaving the oven and tasting the homemade cinnamon buns, donuts, and cookies I made for them.

I may never experience that time with them again, which makes me appreciate it even more.

If you are enjoying MARK. Set. Go… will you please share it with friends and family? I am grateful for your continued support. See you next week.